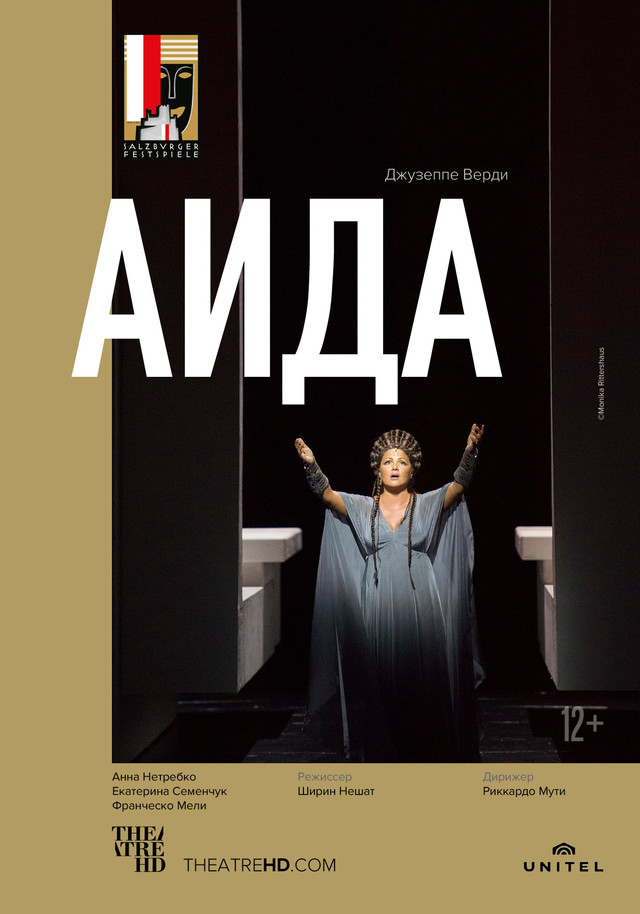

Salzburg-100: Aida

Year: 2017

Country: Austria

Conductor: Riccardo Muti

Director: Shirin Neshat

Set designer: Christian Schmidt

Costume Designer: Tatyana van Walsum

Lighting Designer: Reinhard Traub

Cast: Anna Netrebko, Ekaterina Semenchuk, Francesco Meli, Dmitry Belosselskiy, Luca Salsi

Genre: opera

Runtime: 181 min.

Age: 12+

Country: Austria

Conductor: Riccardo Muti

Director: Shirin Neshat

Set designer: Christian Schmidt

Costume Designer: Tatyana van Walsum

Lighting Designer: Reinhard Traub

Cast: Anna Netrebko, Ekaterina Semenchuk, Francesco Meli, Dmitry Belosselskiy, Luca Salsi

Genre: opera

Runtime: 181 min.

Age: 12+

Passionate and unconditionally dedicated, Anna Netrebko makes her role debut as Aida at the Salzburg Festival, joined by Francesco Meli as Radamès and Ekaterina Semenchuk as her rival Amneris.

‘I must love him, yet he is an enemy, a foreigner!’

After the war is before the war. For one war follows another: wars between neighbouring states, between power elites or potentates, not infrequently approved and supported or even pursued by the religious leaders of various countries. Naturally this demands the commitment and devotion of a country’s subjects as well as the absolute loyalty of the latter to the interests of the state. There is no place for individual life plans, differing ideas of morality or even feelings. Instead, man (and not only the little man on the street) is caught between the wheels of the various interests of those in power. That is one of the stories told in Verdi’s opera by Aida, Radamès and Amneris as well as by their actual and spiritual fathers, the (nameless) King of Egypt, Amonasro and the High Priest Ramfis.

Another story tells of merciless family constellations, such as how the younger generation are made to suffer from the consequences of parental decisions and acts and are driven through no fault of their own into intractable conflicts (of conscience). It is impossible to say who is most affected by this. Aida, who has to live at the Egyptian court as a slave, because she is the daughter of Egypt’s foe, the king of Ethiopia? Plagued by feelings of guilt, she has fallen in love with the captain of the Egyptian guard, Radamès, and is being used by her father Amonasro, to discover the military strategy of the hostile army. Or is it Amneris, the daughter of the Egyptian king, who fights tooth and nail but in vain for her love for Radamès? While ruthless in her attempts to neutralize her rival Aida, she is forced to realize in hindsight that she herself is also the victim of a merciless cartel of power composed of priests and warriors. Or is it the young Radamès, who serves the paternal authorities with such perfection and success but ultimately founders in his struggle for private happiness and is punished by these selfsame ‘fathers’ with death?

Another story tells of merciless family constellations, such as how the younger generation are made to suffer from the consequences of parental decisions and acts and are driven through no fault of their own into intractable conflicts (of conscience). It is impossible to say who is most affected by this. Aida, who has to live at the Egyptian court as a slave, because she is the daughter of Egypt’s foe, the king of Ethiopia? Plagued by feelings of guilt, she has fallen in love with the captain of the Egyptian guard, Radamès, and is being used by her father Amonasro, to discover the military strategy of the hostile army. Or is it Amneris, the daughter of the Egyptian king, who fights tooth and nail but in vain for her love for Radamès? While ruthless in her attempts to neutralize her rival Aida, she is forced to realize in hindsight that she herself is also the victim of a merciless cartel of power composed of priests and warriors. Or is it the young Radamès, who serves the paternal authorities with such perfection and success but ultimately founders in his struggle for private happiness and is punished by these selfsame ‘fathers’ with death?

Aida is Giuseppe Verdi’s third-last opera – it was to be followed, at lengthy intervals, only by his two Shakespeare settings, Otello and Falstaff. It is a well-known fact that Aida premiered successfully at the newly opened opera house in Cairo in 1871. The persistent claim that it was composed for the opening of the Suez Canal is, however, incorrect; Verdi was merely asked to write an inaugural hymn but declined the commission, making it clear that he was not a composer of ‘occasional pieces’.

The initiators of the commission for Aida were the Egyptian khedive Ismail Pasha with his wish for a work that was based on purely Egyptian sources, and the famous French archaeologist Auguste Mariette, who before penning the first Aida scenario had excavated half of ancient Egypt. During his preparations for the opera Verdi had also informed himself about Egyptian geography, religious traditions and ancient musical instruments, something that found expression in the so-called Egyptian trumpets that were fabricated specially for the famous (or perhaps notorious) Grand March and in their outward appearance resemble ancient Egyptian instruments. If you listen attentively to Verdi’s music, however, it is obvious that the composer was concerned not with ‘musicalized’ history but – as in so many of his operas – with a critique of an inhuman society, this time in Egyptian clothing.

The initiators of the commission for Aida were the Egyptian khedive Ismail Pasha with his wish for a work that was based on purely Egyptian sources, and the famous French archaeologist Auguste Mariette, who before penning the first Aida scenario had excavated half of ancient Egypt. During his preparations for the opera Verdi had also informed himself about Egyptian geography, religious traditions and ancient musical instruments, something that found expression in the so-called Egyptian trumpets that were fabricated specially for the famous (or perhaps notorious) Grand March and in their outward appearance resemble ancient Egyptian instruments. If you listen attentively to Verdi’s music, however, it is obvious that the composer was concerned not with ‘musicalized’ history but – as in so many of his operas – with a critique of an inhuman society, this time in Egyptian clothing.

Aida is ‘Verdi’s finest work’, wrote the contemporary composer Dieter Schnebel, praising its music as expressing a ‘warm humanity that translates the human suffering of the individual and the many in nature and the world into an artistic utopia of tragic beauty and beautiful tragedy’.

Вадим Рутковский

2 September 2021

Опера «Аида» с Анной Нетребко в заглавной партии – в кинотеатрах страны